'My People'

Edward Abbey's Appalachian Roots in Indiana County, Pennsylvania

by James M. Cahalan

Part II, Section 5 : Abbey's Visits Home

Indeed, while he spent most of his life in the West after 1947, Edward Abbey returned home in person -- not only in his writings -- on many occasions. In his journal on his 25th birthday in 1952, while studying on a Fulbright scholarship in Edinburgh, he wrote of "returning home, climbing the green hill through fields and over wild places of grass and briars and down the hill through the heavy green woods and across the little stream of water from the pasture and under the great maple tree and through the kitchen's open door to the final triumph and tragedy that has never failed me and will never fail me -- returning home" (Confessions, 18). The home he remembered was the Old Lonesome Briar Patch, and he seemed to much prefer his earlier visits there to his later visits at the much smaller house that his parents moved into in 1967, along the busy highway through Home. In October 1952, back at the Briar Patch, he could write poetically about how "the proud immortal American autumn seems finished -- the gold and death-fire of leaves is gone -- all is black, drab lusterless brown, gray under a bleak smoky sky" (Confessions, 102). Seventeen years later, in October 1969, while visiting his parents little house along the busy highway his impressions were different:

Back home, where you can't go, said Wolfe. Why not? Says Wendell Berry. I'm with Wolfe. To me, this town, this place, this area is nothing. I feel nothing, no emotion whatever. Might as well be visiting Fargo ND for all it means to me. Everything has changed. No, not everything -- but much. The town is now three times bigger. Pittsburgh is much closer; only an hour's drive away with Indiana now practically a suburb. New houses all over the hills outside town -- devastated farmland -- hills disemboweled to make room for highway interchanges -- new factories and coal-burning power plants -- the old teachers' college is now ten times grown and called a "university" -- schools and children everywhere. The post-war baby boom has exploded on us now. All the old-style general farms are gone; the only serious farmers now are specialists: dairy beef, pigs, truck, Christmas trees, cabbages. Most work their farms only on weekends; work in stores or factories the rest of the time. A dismal scene, man. (Confessions, 223-24)

Ed Mears remarks, concerning his old friend's visits, that "he expected this to be the same as it was when he left. And I kept saying, 'Ned, everybody and everything changes. When you're away from here eight to ten years, the people here change.' Well, he was disappointed because the people had changed and I said, 'Well we've all changed. You've changed.' And it seemed like it bothered him that this area had changed." Concerning the various forms of "development" that he saw, Abbey told Mears, "'Well, it's all right to do it back here, but we don't want anything west of the Mississippi.' He said, 'They should've put a barricade up when we got to the Mississippi. Nobody would've gone west of that.' That was his theory."

On December 5, 1969, the year after Desert Solitaire had been published, Abbey was presented with an "Ambassador Award" by the Indiana County Tourist Promotion Bureau at a banquet at the Rustic Lodge. Sam Furgiuele was there:

When they gave him the plaque, he stood up, a kind of imposing guy and looked at the plaque, turned it around, grinned, turned it around and looked at it the other way as if to make it very clear that this didn't mean a thing to him. Then, literally he simply tossed it the way you would do a magazine or a card onto the table. His first words were, "You must know I don't believe in professional tourism." He said in effect that there should be no need for a professional tourist bureau or tourism if you did the things in a community that you ought to do. And he went through and he named some things that he thought should be done in Indiana. For example, he said, "Make it beautiful. Make it beautiful and people will come to it." He said, "Get that goddamn traffic off main street and build a parkway down there," which was a tremendous idea. "Put some benches in there; plant some trees." Well, some of the guys we know were extremely upset with his abrasiveness in his attack on the community leaders and on the Chamber of Commerce. They were saying they're giving him this recognition and he should have been gracious enough to accept it like a gentleman. Well, you know, I respected Ed for what he did because what he was saying was true.

I got to see the plaque that was presented to Abbey, because it ended up in his brother Howard's basement; Ed didn't bother to take it home, back west, with him.

His visit to the home of IUP English professor Raymona Hull, to speak to her class during the same December 1969 trip, was no more of a popular success. She told me that the students were overawed, Abbey seemed ill at ease, and afterwards when she asked if he would like some refreshment, he requested a beer; she had none to offer since it was a freshman class, and finally an older student took Abbey out to a bar. "I think the whole interview was a disaster ... I felt as if there was a universal sigh of relief when he left."

Abbey's old friend John Watta took the lead in bringing Abbey back to IUP to speak on several occasions during the 1970s and early 1980s:

I'd have to drive to Pittsburgh to pick him up at the airport and then, of course, lots of stops along the road, where we would slake our thirst. I got the impression all the time that I was with him that he was a vicious, nasty sort. And then that was all done away with in that one thing when I drove him home, to his parents' home there, and I was trying to get the car turned around and he walked inside and then through the window I saw him and his mother, embracing. There's that tough guy. And my heart went out to him because there was a different Edward Abbey.

Really rather shy by nature, Abbey developed a quite different, strong persona as a public speaker during these years. This was the case not only because he was the sort who was determined to speak the truth (more or less), but also because he got more and more requests to speak and carefully wrote out his lectures before giving them. In January 1968, Abbey could complain in his journal of being "America's most famous unknown author" (Confessions, 211), but by November 1976, after the publication of Desert Solitaire (1968) and The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975), he wrote about "becoming a 'cult hero"' (Confessions, 246).

On December 9,1976, Abbey lectured at IUP to an audience that included his parents. Here are a few of the most remarkable highlights from the manuscript of his lecture in the University of Arizona archive:

Last time I gave a talk in Indiana was seven years ago, 1969, before a gathering of some of Indiana's most distinguished citizens. They said they were making me Indiana County's ambassador to the world .... It was a very moving little speech -- about half the audience wanted to move right out of the hall .... I was born and raised near Home, Pa., ten miles north of here on Highway 119. Home -- population 110, not counting dogs and chickens. My parents still live there, God bless them, where they always wanted to live, in a little house by the side of the road. ... Where is home? What is home? Thomas Wolfe said you can't go there again. Typical displaced romantic -- like myself ... A writer down in Kentucky named Wendell Berry asks why can't you go home again? He has done it and found his place. Others say home is where you have your roots . ... But I too have found my home. And I define it thus: home is where you have found your happiness .... There are some -- many -- who never make this discovery for themselves, who spend their entire lives in the search for a home .... Such people are not hard to identify: they are the ones who will sell their native acres for easy money; who will strip-mine and clear-cut and flood with dams the place where they were born.... We know the type; they generally run things .... Though I've lived most of my life so far in the red and gold of the American Southwest, and think of myself as a desert rat and a Southwesterner, I'll never get the green of Appalachia out of my heart. Nor ever want to. These misty hills will always be a part of my life, the source of my earliest inspiration. And I want to take this opportunity -- I may never get another -- to pay tribute, publicly not only to this place, but to certain people in this place, who taught me so much, to whom I shall always be in debt. I mean certain teachers -- Ray Munnel of Marion Center High, Lambert Joseph and Mary McGregor and Art Nicholson of Indiana High, Rhodes Stabley of Indiana University of Pennsylvania, then called ISTC. Most of all I want to pay homage to my mother, Mildred Abbey, who taught me to love music, and art, and poetry, and to my father, Paul Revere Abbey, who taught me to hate injustice, to defy the powerful, to speak for the voiceless.

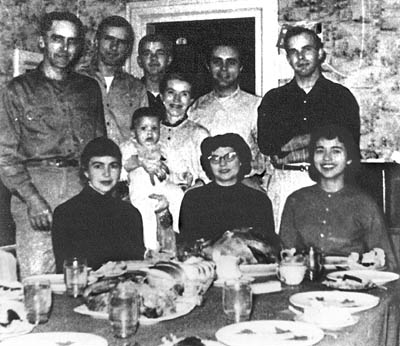

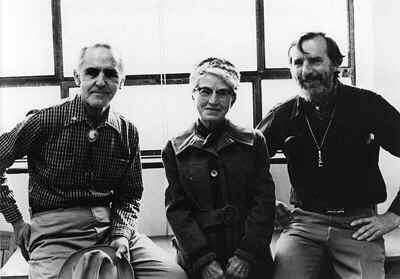

Parents Paul and Mildred with Abbey during his December 1976 appearance at IUP, where he paid special tribute to them for their equal but radically different influences. Abbey has not yet been given sufficient recognition in his native county. In April 1983, he was honored as one of four "IUP Ambassadors," but notice of this award in the Indiana Gazette got lost in local media feeding frenzy surrounding the special day of another local -- Jimmy Stewart, whose 75th birthday party included the unveiling of a larger-than-lifesize statue in front of the Indiana County Courthouse.[49] The contrast between Abbey's reputation out west versus his reputation in his native county is underscored by the fact that after his death in 1989, the Tucson Weekly devoted a magazine supplement to Abbey, while the Indiana Gazette limited itself to a single obituary.[50]

Next section: Appalachian Themes

Notes

[49] Abbey was one of the four IUP alumni ambassadors honored in April 1983; the Gazette did run a front-page photo on April 29 with the caption "IUP Ambassador -- Writer Edward Abbey back at IUP to be designated an IUP Alumni Association Ambassador this weekend is shown reading some of his materials and talking to a group of students last evening in Pratt Hall." ("IUP Ambassador," Indiana Gazette, 29 April 1983, 1) But then he got lost in front-page coverage of "Stewart/Indiana Delegation at Statue Unveiling," Indiana Gazette, 2 May 1983, 1; one has to turn to p. 15 of that issue to find passing mention of Abbey's honor, and even there Abbey is merely listed among 14 other IUP students, as a "distinguished author" ("Outstanding Alumni, Two Seniors Honored at IUP Alumni Weekend," Indiana Gazette, 2 May 1983, 15, 26). Abbey got one phrase about his visit; Stewart, most of the front page, before his visit had even occurred. The Gazette then devoted almost daily coverage to Stewart from May 12 through his visit on May 20-21, including a full-page spread on a Stewart film festival ("Relive Jimmy's Classic Movie Career at Film Festival," Indiana Gazette, 16 May 1983, 13) and a 40-page insert on May 19 dedicated to his whole life ("It's a Wonderful Life," Indiana Gazette, 19 May 1983, insert 1-40). After all the fuss over Stewart finally began to quiet down, the Gazette did finally run three belated articles in the following month: "Faculty Names Abbey Alumni Ambassador" (10) on 14 June and, on 18 June 1983, "Edward Abbey Returns Home" and "Paul and Mildred Keep Up the Pace" (n. p.).

[50] "A Celebration of Edward Abbey", 12-page special magazine supplement, Tucson Weekly, 5-11 April 1989; 'Author Dies in Tucson," Indiana Gazette, 15 March 1989, 1, 4.

Why ads for Amazon?