'My People'

Edward Abbey's Appalachian Roots in Indiana County, Pennsylvania

by James M. Cahalan

Part I, Section 1 : Introduction

"The foothills of Appalachia at last. Now we're getting somewhere.... My people."

-- Edward Abbey, The Fool's Progress (459-60)AUTHOR OF MORE than 20 books, native Western Pennsylvanian Edward Abbey (1927-1989) became internationally known as a writer and a champion of the canyons and deserts of America's Southwest.

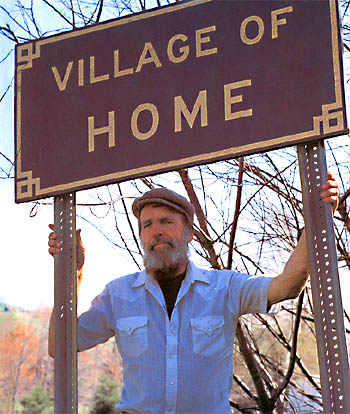

Edward Abbey often said he was born in Home, Indiana County, although he wasn't. As a child he did live in this village with the perfect name (and he posed there on a trip Home in 1986). Abbey was born and grew up in Indiana County; about 60 miles northeast of Pittsburgh, and spent nearly all of his first 21 years there. His parents were also from the region, and several of his relatives still live in Indiana County. Ed Abbey's writing attracted a popular, even cult following, especially in the West, but there is a double-edged irony to his fame: he has remained largely unknown in his native Western Pennsylvania, while most of his readers in the West know little about the Pennsylvania heritage that Abbey himself considered crucial to his voice as a writer. Desert Solitaire (1968), a book of essays about the red rock country of Arches National Park and Canyon-lands National Park in Utah, tops some lists as the best twentieth-century book about the natural world. The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975), a novel about four activists who believe in direct action against "development" of wilderness areas, inspired the movement called Earth First! and solidified Abbey's reputation as an aggressive opponent of federal land use policy.[1] Larry McMurtry, author of Lonesome Dove and other fictional works set in frontier days beyond the Mississippi River, has called Abbey "the Thoreau of the American West."[2]

This article aims to redress the circumstance that Abbey is so little known in his native region and that the significance of the area to him and his work has been little appreciated even by those who know Abbey's books. Drawing on interviews with more than 20 people (mostly in Indiana County), more than a thousand pages from the Abbey archive at the University of Arizona in Tucson, and my reading of his writing (both published and unpublished), I hope to encourage an understanding and appreciation of Edward Abbey. Because scholars and fans of his writing largely have missed the significance of his heritage, I also want to tell as much of Abbey's Western Pennsylvanian story as possible. Basic facts about his years in the area are not widely known, while others have been reported wrongly An example is his birthplace -- reported incorrectly until now as Home, Pennsylvania.[3]

I will focus mostly on Abbey's life, and draw on his writings as part of his life story.[4] Western and environmentalist readers have long considered Abbey's books instructive. But Western Pennsylvanians may learn a lot about themselves and their world, as well, from Edward Abbey.

Abbey the novelist in the mid-'60s, after three books. His next and most famous work was non-fiction: Desert Solitaire. The value of Abbey's work has been recognized for more than a quarter of a century. Abbey won a Fulbright Fellowship to Edinburgh University in Scotland in 1951, a Wallace Stegner Creative Writing Fellowship to Stanford in 1957, and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1974. He also enjoyed popular and critical success. Kirk Douglas turned Abbey's second novel into Lonely Are the Brave (1962), which Douglas says is still his favorite movie, and he eulogized Abbey in the Los Angeles Times.[5]

Yet Abbey always felt that the New York literary establishment ignored and mistreated his efforts, and he could be cranky about receiving awards. When Irving Howe invited him to a banquet inducting him into the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1987, Abbey wrote back. "I appreciate the intended honor but will not be able to attend the awards ceremony on May 20th: I'm figuring on going down a river in Idaho that week. Besides, to tell the truth, I think that prizes are for little boys. You can give my $5,000 to somebody else. I don't need it or really want it."[6]

Several books about Abbey and his work have already appeared and are still coming out, and he has been written about in French.[7] The Abbey collection at the University of Arizona contains 30 large boxes of almost every imaginable kind of archival material, so scholars have ample resources for many more articles and books. All of his books have remained in print except for his first novel (Jonathan Troy, 1954), which Abbey disdained and refused to have reprinted -- and so that novel has become quite a collector's item. A bookstore manager in the Southwest tells me that he would not consider selling his used copy for any price below $1,000, and some people have obtained the novel via inter-library loan and then deliberately failed to return it.

On the Internet, Abbey is the subject of a very active "abbeyweb," which is a "listserv" discussion group, and "Abbey's Web," one of the most elaborate and highly rated sites on the World Wide Web. Both were created by Christer Lindh, whose account of how he came to devote himself to Edward Abbey is illustrative of the kind of devotion that Abbey continues to attract:

Abbey's Web is reachable from anywhere in the world via the Internet, but it is physically located on a computer in Stockholm, Sweden, of all places, and is written and maintained by me, a Swedish software engineer. The obvious question is, Why me?... One day a friend gave me a book to read; it was called Desert Solitaire and it was written by one Edward Abbey. That evening I read it from cover to cover. I was hooked by his writing, with its unique combination of beautiful descriptions of the desert and a biting wit that attacks the forces that would destroy it. The next weekend I ventured out on my own to try to find the magic of the desert that had obviously eluded me so far. I found it. This experience fueled my metamorphosis from a computer nerd to an outdoor enthusiast and nature-defending nerd... Before returning to Sweden in October of 1989, I took a month-long trip through southern Utah, northern Arizona, and the eastern Sierra Nevada. Along the way I read more books by Edward Abbey and got even more firmly hooked when I had a chance to see and feel the areas he loved and fought for.

Abbey's web site is filled with admiring comments by readers from throughout the world. Two quick, typical examples can suffice: "Memorize Desert Solitaire. Carry it around. Make it your life," and "Ed Abbey came into my life many years ago via The Monkey Wrench Gang. Since then I have acquired nearly all his books and he remains my favorite author. I can't count the number of times I've given Desert Solitaire to others to read. I miss him."[8]

From an early age, Abbey showed an intense interest "the West." Note the toy revolver in his grasp. The son of Paul and Mildred Abbey, and the oldest sibling of Howard, John, Nancy and Bill Abbey, Edward Abbey was born January 29, 1927. Except for a two-year hitch in the Army between 1945 and 1947, he lived in Indiana County before moving to the west in 1948. He returned home to visit his relatives many times in his life. His Appalachian heritage in Western Pennsylvania comes up repeatedly in his writings, even in books set entirely in the West. Jonathan Troy, whose namesake is an autobiographical high school student, is set entirely in and around the town of Indiana (fictionalized as "Powhatan, Pennsylvania"), which Jonathan finally leaves, hitch-hiking west, at the end. The novel he considered his magnum opus and called his "fat masterpiece," The Fool's Progress (1988), which he struggled to write for many years, concerns the boyhood and eventual return home of his autobiographical protagonist, Henry Lightcap. Here Indiana is thinly disguised as "Shawnee, West Virginia," and the area eight to 10 miles north of the town in Indiana County where Abbey grew up becomes "Stump Creek" (an actual village midway between Punxsutawney and DuBois, Pennsylvania).

Abbey's desire for recognition in his native place is reflected late in The Fool's Progress when Henry comes upon a historical marker: "Shawnee... Birthplace of Henry H. Lightcap" (498). Yet when I made my first phone call to propose such a historical marker for Abbey in his native county, the reaction was "Who's Edward Abbey?" (Robert Redford, who knew Abbey, and others wrote letters of support for this marker. It was approved by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, and it was dedicated in September 1996 on U.S. 119 in Home.)

The campaign for an Abbey historical marker in Home, Pa. (erected in September 1996) was spearheaded by this article's author. Abbey himself remarked that his least favorite categories of incoming mail included "letters addressed to Edward Albee," from readers wondering why The Monkey Wrench Gang was so different from Albee's The Zoo Story. In Indiana County and in Pennsylvania in general Edward Abbey, so acclaimed elsewhere as a writer and environmentalist, has tended to get lost in the shadows of his more glamorous fellow Indiana native Jimmy Stewart. Stewart left Indiana for good at the same age as Abbey but his return for his 75th birthday celebration in 1983 dominated the Indiana Gazette for months, and the Jimmy Stewart Museum (occupying the entire third floor of the town library) was opened with similar fanfare in 1995, when the actor was still very much alive.

In contrast, a majority of people in Indiana County have never heard of Edward Abbey. Yet there are certainly more than enough people in the area who knew Abbey and his family including his two surviving brothers, to set the record straight.

Edward Abbey's Books Nonfiction

- Desert Solitaire, 1968.

- Appalachian Wilderness, 1970.

- Slickrock, 1971.

- Cactus Country, 1972.

- The Journey Home, 1975.

- The Hidden Canyon, 1978.

- Abbey's Road, 1979.

- Desert Images, 1981.

- Down the River, 1982.

- Beyond the Wall, 1984.

- One Life at a Time, Please, 1987.

- A Voice Crying in the Wilderness: Notes from a Secret Journal, 1989.

- Confessions of a Barbarian: Selections from the Journals of Edward Abbey, 1951-1989, 1994

Novels

- Jonathan Troy, 1954.

- The Brave Cowboy, 1956.

- Fire on the Mountain, 1962.

- Black Sun, 1971.

- The Monkey Wrench Gang, 1975.

- Good News, 1980.

- The Fool's Progress, 1988.

- Hayduke Lives!, 1990.

Anthologies

- The Best of Edward Abbey (also published as Slumgullion Stew), 1984

- The Serpents of Paradise: A Reader, 1995.

Poetry

- Earth Apples, 1994

Next section: Abbey's Early Life

Notes

[1] In 1981, Abbey spoke to Earth First! demonstrators at the Glen Canyon Dam who rolled a huge, symbolic, plastic "crack" down the middle of the dam. Since 1966, this massive dam has flooded the Colorado River above the Grand Canyon, disturbing the ecosystem by slowing the river, and turning Glen Canyon, a once equally beautiful area containing ancient Native American rock drawings and dwellings, into Lake Powell. (Abbey and his followers called it "Lake Foul.") When Abbey died in March 1989, his friends and admirers were so upset that they had not one, but two large public wakes in his honor, the first soon after his death at Saguaro National Park near his home in Tucson, and the other in May at Arches. After he was buried by a few of his closest friends somewhere in the desert at a site known only to them and his wife, they put piles of rocks at some other places in the Southwest because they were afraid that cultists would find and disturb his burial site. See Edward Hoagland, "Edward Abbey: Standing Tough in the Desert," The New York Times Book Review, 7 May 1989, 41.

[2] McMurtry's descriptive phrase has been cited in myriad places; one example is Brad Knickerbocker, "The Values and Philosophies of Great American Nature Writers," The Christian Science Monitor, 10 Aug.1994, 13.

[3] James Bishop's biography contains some errors about Abbey's birth and his family. Not only does he claim that Abbey was born in Home (xi) -- in fact, Abbey was born in Indiana Hospital -- but, for example, he seems unaware of the continued existence of Bill Abbey, referring only to Abbey's "surviving siblings, Nancy and Howard" (xv) and "Howard Abbey, Ed's surviving younger brother" (56). A photograph that is actually of Bill Abbey, Nancy Abbey, Iva Abbey, Mildred Abbey, and Ed Abbey, taken at John Abbey's funeral in 1987, is captioned by Bishop as "Brother Johnny Abbey, sister Nancy, a friend, and mother Mildred, 1986." Bishop also mistakenly asserts that Mildred Abbey died in 1987 (56). She was killed by a truck in an accident in Nov. 1988.

[4] My article "Edward Abbey, Appalachian Easterner," in Western American Literature 31.3 (Nov.1996): 233-53, focuses on Abbey's writings, especially Jonathan Troy, Appalachian Wilderness, and The Fool's Progress.

[5] Douglas, "Death of Writer Edward Abbey," Los Angeles Times (Abbey collection, no date). Douglas wrote that when he read Abbey's novel, The Brave Cowboy, around 1960, "I was deeply moved. I bought the movie rights and finally persuaded Universal to allow my company, Bryna, to make the film, which was brilliantly written by Dalton Trumbo and produced by Eddie Lewis. In the cast with me were Gena Rowlands, Walter Matthau, and William Shatner, and introducing Carroll O'Connor in a small role... I apologized to [Abbey] that the studio insisted on changing the title ... to Lonely Are the Brave. In the more than 80 films that I've made, this is my favorite." I am very grateful to Clarke Cartwright Abbey for her permission to study, copy, and quote from the Abbey collection, and am also very thankful to Roger Myers, Peter Steere, and their assistants in the Special Collections Department of the University of Arizona library for all of their invaluable and copious assistance.

[6] Abbey letter of 20 March 1987, Abbey collection, University of Arizona Special Collections, box 3, folder 18.

[7] See, for example, Garth McCann, Edward Abbey (Boise, 1977); Ann Ronald, The New West of Edward Abbey (Albuquerque, 1984); James Bishop, Jr., Epitaph for a Desert Anarchist: The Life and Legacy of Edward Abbey (New York, 1994); and Frank Stewart, A Natural History of Nature Writing (Washington, D.C., 1995). Overviews of criticism on Abbey may be found in Contemporary Authors, vol.45; Contemporary Authors: New Revision Series, vol. 41; and Contemporary Literature Criticism, vols. 36 and 59. The criticism in French is by Sylvie Mathe: "Méditation sur le Désert: Figures et Voix," in Mythes Ruraux et Urbains dans la Culture Américaine (Marseille, 1990), 135-55.

[8] Abbey's web site can be found on the World Wide Web at: http://www.utsidan.se/abbey/; Christer Lindh, "Weaving Abbey's Web'," Arid Lands Newsletter, issue 38, at http://www.utsidan.se/abbey/abbey-Weaving.html; the two readers' comments, at http://www.utsidan.se/abbey-Desert.html#Heading52.

Why ads for Amazon?